A conversation that has always stuck with me is when about a decade ago Jeb Bush remarked that in terms of electoral politics education hadn’t really helped him at the state level. He basically did his politics elsewhere, he said, and did education because it was a policy area he cared about. Florida under Bush is one of the education success stories of the past quarter century. Yet that didn’t really help him when he ran for president. Elite journalists respected it, as did the wonks. The average Republican primary voter? Meh. His education record – validated by NAEP and independent evaluations – led to more success for his non-profit education policy organization than in national political races.

Sure, education can help you electorally. Jeb’s brother George used the issue to signal to voters that he wasn’t slash and burn like Newt Gingrich or Tom DeLay. Earlier Bill Clinton used education reform and support for charter schools to cue voters that he was a “new” kind of Democrat, not beholden to party orthodoxy. But that’s framing, not policy specifics. Even today a lot of voters are confused about what charter schools are so in 1992 you can be sure most were more attracted to the new and reform flavor of the idea than the policy.

The first President Bush actually worked with then-governor Clinton on education policy reform at a landmark summit in Charlottesville, Virginia. A lot of good it did him. And Clinton’s two terms had more two do with economics and social policy reform than with specific education policies under his watch. Ironically, one of Clinton’s most politically popular reforms, class sizes reeducation, wasn’t a great one on the specifics but allowed him to beat the hell out of Republicans in budget fights. George W. Bush’s presidency faltered on foreign adventures. No amount of education results or policy, no matter how much they cut against type for Republicans could offset that.

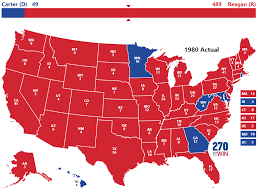

Jimmy Carter? He set up the modern Department of Education and got 49 electoral votes in 1980 for his trouble. Lyndon Johnson? He was pretty good on education but when more than 1,000 Americans a month are dying in Vietnam that hardly matters. You get the idea: At the national level elections generally turn on economics or other macro factors.

In practice, for the most part education is one of those political issues that is almost all downside – even when you get it right. That’s not just because kids are too young to vote or people who lack political power and need educational power lack political power. Those are obvious reasons. It’s also because, in plain terms, there is more downside to the risk than upside to the success. And success takes time to show itself and the benefits of success are diffuse. The political hits? They are mostly in the here and now. They are concentrated. Politicians are understandably concerned with the here and now and with concentrated power, because that’s what drives politics.

A few obvious examples.

Assessment reform and innovation is a vital issue but it mostly leads to attacks that you’re for more testing or spending more on testing. Sure, strong majorities of Americans get that testing is a transparency, empowerment, and accountability tool. Yet there is no nuance there even though large scale assessment is complicated and nuanced because organized resistance to assessment is potent. That’s why politicians like Beto O’Rourke, who is certainly smart enough to know better, campaign on just getting rid of rests.

Education standards. Time in school is not infinite, so choices have to be made about what framework is important for students to know by the time they leave high school. Otherwise you get meaningless standards teachers can’t use because they’re too vague or demand more time than schools have. But almost everything left out will be important to someone. They will argue about it and often attack politically. It’s an unwinnable battle in the here and now. What’s more, little credit accrues to having good standards.

Common Core. A lot of states quietly shifted to Common Core-like standards and behind the scenes even some Republican governors tried to keep the train on the tracks. That’s hard because “Common Core” remains a political punching bag. That’s a real problem for a politician who wants to at once improve schools but stay politically viable in a climate where both right and left are upset about the new standards.

Teacher evaluation or accountability. You can certainly argue that trying to shift from evaluating basically no one to evaluating everyone on a fast time table was going to cause problems. I argued that! But politically there is a reason accountability of any kind is so hard. Present costs, that are concentrated, future benefits that are diffuse. Little credit for getting it right, lots of pain for getting it right or wrong.

All this is because most education policy runs into the classic problem of the general interest versus special interests in a political system where the general interest is diffuse and disorganized, the special interests are concentrated and organized. In many cases, especially in education, special interests have more power and interest for punishing for transgressions than rewarding for taking risks. This is a problem on all issues, not just education. It affects gun policy or tax policy, too. And despite the happy talk, there are no win wins. In our sector, more school choice means more power for parents and less for school systems. More accountability means more information for parents and the public but less control of that information by school systems. People use lots of vague language to try to straddle these tensions but at the end of the day every major decision represents a shift of power from one constituency to another.

So is it hopeless? No, I don’t think so.

School choice is something of an exception here. Choice builds a constituency of satisfied parents. Politically its greatest hurdle is initial enactment. It also disrupts systems of power. But school choice, too, activates substantial special interest opposition. That makes it a challenge of electoral politics, less of governmental politics. Yet as the lines between those two kinds of politics become increasingly blurred (or even unrecognizable) it can still be a challenge. Years ago the teachers union in Indianapolis decided to go to the city council to make a run at ending the (Democratic) mayor’s charter school initiative there. Hundreds of parents showed up to support the charters. That was more or less the end of that and Indianapolis parents continue to enjoy a lot of choices. There is a lesson there.

In addition, voters still reward competence. Joe Biden didn’t win in 2020 because voters had suddenly decided Washington, DC and the federal government were OK after all. They just could see that Donald Trump was manifestly incompetent. That’s why in a state like Virginia – with a lot of federal and military personnel – Biden could run up big margins one year and Glenn Youngkin could be elected governor the next. And Youngkin’s win was in part about education pragmatism. Here in education, the biggest problem with George Bush’s No Child Left Behind policy was Bush’s Iraq War policy. It was, and still basically is, impossible to get a fair hearing on the NCLB policy or an accurate accounting of it – did you know Ted Kennedy clashed with Bush on the funding but not on the accountability rules? Clinton’s handling of education made him look pragmatic and competent. The pundit class ridiculed Clinton’s idea of school uniforms, parents loved it. We’ll see what happens but in Pennsylvania Josh Shapiro seems to have taken heed of this lesson.

So if you’re an advocate, parent empowerment and choice are good ways to go. They build constituencies. If you’re a politician competence is – and that includes trying to balance competing pressures in education rather than just pandering. That’s how you reap any upside there is to education politics. Just be pragmatic and do a good job. Another thing Clinton used to say is that good policy is good politics. It’s unfortunately not that simple or linear, but on an issue like education it’s the best bet you have. Otherwise, politically, it’s mostly downside.