Today at the Supreme Court arguments were heard in two cases involving race-based affirmative action, one from North Carolina and a higher profile case against Harvard. A lot of people are saying it’s the most important case(s) of the court’s current term. I guess I disagree with that in the sense that an important case seems to me like one where the outcome is in question. Given the composition of the court today, and how these cases moved to the high court, this one seems over except for the part where the justices vote. In 2003, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor said affirmative action would be gone in 25 years. As in many other ways she was ahead of her time.

The outcome of today’s case will certainly be symbolic. It will fuel arguments about our politics and about the court (though unlike Dobbs this will not be a countermajoritarian decision). I’m not sure, however, how substantively important it will be.

Much of American history is a story of laws being passed on behalf of Black Americans and then those laws being ignored. The importation of slaves was banned in 1808, but it continued right up until the eve of the Civil War.* When Union troops left the South after Reconstruction, in addition to ushering in a new era of racial terror and formal racial caste system, all manner of laws and constitutional protections were ignored and flouted. We’ve made remarkable progress, of course, but these problems are not a relic of the 19th-Century. As anyone who has opened a newspaper in the last decade knows, reckoning with this part of our history – the good and the bad and the present impact – is something we still struggle with.

But, somewhat paradoxically, I’m less concerned about these affirmative action cases than some are because I expect the law to be somewhat ignored here, too. That’s because a few things are true.

First, college admissions are opaque and affirmative action is already somewhat curtailed today. Unless you go to a purely test-based system, which no one does, a lot of factors go into admissions. At public universities factors like where a student is from in a state or if they are out of state, choice of major and school, and diversity all factor into these decisions. Admissions are not a decision of are you in or out overall, so much as how does an applicant stack up in various pools of applicants- for instance against other out-of-state engineering applicants at a public university. It’s even more opaque for private schools – especially elite privates like Harvard. Besides, most colleges in this country take anyone who applies, selective schools are a small fraction of what’s on offer and not the experience for most Americans who attend college. Affirmative action gets a lot of attention in part because it’s about the elite schools we fetishize.

A ruling striking down affirmative action will probably rein in the excesses but not be the death knell for racial and ethnic diversity in higher education that some fear simply because it’s hard to say why a lot of decisions are made. And also, of course, the country is diversifying anyway.

Another reason the impact might be more limited is because, second, Americans don’t like formal race-based affirmative action but value diversity. When affirmative action is put to the test at the ballot box it doesn’t do well – even among non-white Americans. Most recently, the defeat of affirmative action in California in 2020 should have made that abundantly clear. Yet at the same time, in general, Americans do like diversity – of all kinds it should be noted not just race and ethnicity. There are some methodological problems with this poll from earlier this year (party ID and question wording for instance), but it does broadly point in the direction that people value diversity. The poll also underscores how elite advocacy groups need to engage with the broader sentiments in this country – which are again not hostile to diversity but don’t like what seem to be rigid formal systems for achieving it. In their hearts a lot of Americans want diversity, in their heads they are with Hayek and John Roberts and resist what they see as government sanctioned discrimination. Figure out a way to talk about diversity and preferences that works better at a corner bar than a faculty lounge and you will have a forward moving politics a lot of people can get behind.

Progressive affirmative action proponents are in an awkward spot here because they are stuck simultaneously arguing that affirmative action isn’t really much of a plus factor so it’s not a big issue from a constitutional standpoint and that, also, if we get rid of it then the results will be catastrophic. Conservative opponents are stuck wishing away some of the realities of American life today – including legacy admissions and a profoundly unfair K-12 system that assigns the poor to schools by their zip code.

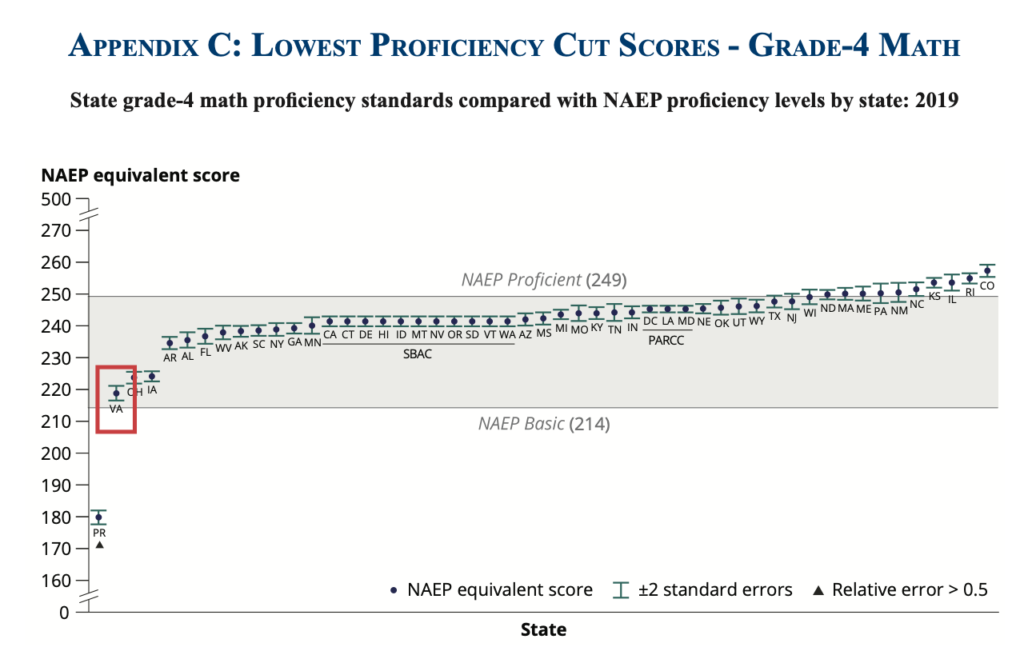

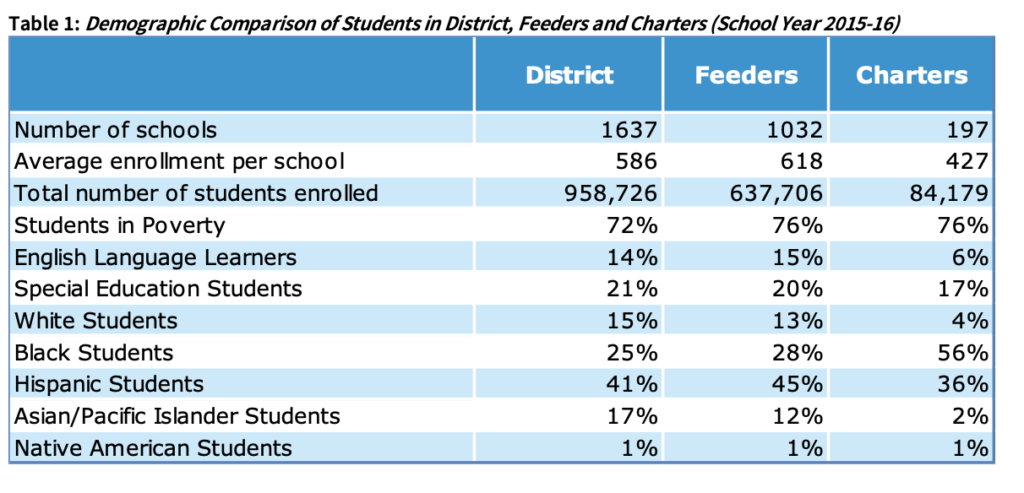

Finally, we know race and class are not the same thing. In plenty of data there is evidence race exerts a special leverage. You see that right here in our K-12 sector. But there is a broad overlap between race and class – and low-income Americans of all races and ethnicities face a lot of structural barriers to opportunity and social mobility. Class-based affirmative action and class-based politics more generally do offer a lot of promise – even if they’re not fashionable in elite spaces. They also bring the promise of more viewpoint diversity. There is some evidence that states that have banned affirmative action have seen declines in underrepresented students, but it’s unclear how much that could be offset by robust class-based measures and other strategies focused on student success. There is plenty of evidence that affirmative action is benefiting economically advantaged students. And obviously we might get serious about improving K-12 schools.

This brings us to Rick Kahlenberg. Rick’s a progressive’s progressive. He and I have disagreed, for instance, on what we should expect from controlled choice plans based on economics relative to charter school plans that increase the supply of public schools. He wrote an admiring biography of influential and iconoclastic teachers’ union leader Albert Shanker that arguably minimized how Shanker’s vision fell short in the meat grinder of union politics. Agree or disagree on issues, Rick’s thoughtful and gets up in the morning trying to figure out how to make America work for more Americans. But as a proponent of economic affirmative action Rick’s on the side of plaintiffs in this case – literally, he was an expert witness as the Harvard case moved through the courts. Whether you agree or disagree with him about that, I’d urge you to read this essay he just wrote in The Atlantic about affirmative action. Among other things, it shows that underneath our partisan and largely tribal debate about affirmative action the current policies aren’t working all that well anyway. Perhaps this decision will usher in new ideas and approaches that move us closer to a more inclusive American across more lines of difference. It does seem like it’s time to try something new.

In any event, Rick’s approach here is a model for principle, for thoughtful disagreement, and also for heterodoxy and how well-intentioned people can look at some questions and come to different conclusions on the best path forward. In general we need more of that if we’re going to get anywhere.

*I think I have recommended it before but just in case, Shemekia Copeland’s “Clotilda’s on Fire” is a callback to the last slave ship known to have arrived on these shores and a highlight of her strong 2020 “Uncivil War” album. One of the enslaved people on that ship became the focal point of a controversial Zora Neale Hurston book.